More than 4,000 years ago the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers began to teem with life--first the Sumerian, then the Babylonian, Assyrian, Chaldean, and Persian empires. Here too excavations have unearthed evidence of great skill and artistry.

From Sumeria have come examples of fine works in marble, diorite, hammered gold, and lapis lazuli. Of the many portraits produced in this area, some of the best are those of Gudea, ruler of Lagash.

Some of the portraits are in marble, others, such as the one in the Louvre in Paris, are cut in gray-black diorite.

Dating from about 2400 BC, they have the smooth perfection and idealized features of the classical period in Sumerian art.

Sumerian art and architecture was ornate and complex. Clay was the Sumerians' most abundant material. Stone, wood, and metal had to be imported.

Art was primarily used for religious purposes. Painting and sculpture was the main median used.

THE WARKA VASE

The detailed drawing above was made from tracing a photograph (from Campbell, Shepsut) of the temple vase found at Uruk/Warka, dating from approximately 3100 BCE. It is over one meter (nearly 4 feet) tall. On the upper tier is a figure of a nude man that may possibly represent the sacrificial king. He approaches the robed queen Inanna. Inanna wears a horned headdress.

The Queen of Heaven stands in front of two looped temple poles or "asherah," phallic posts, sacred to the goddess. A group of nude priests bring gifts of baskets of gifts, including, fruits to pay her homage on the lower tier. This vase is now at the Iraq Museum in Bagdad.

"The Warka Vase, is the oldest ritual vase in carved stone discovered in ancient Sumer and can be dated to round about 3000 B.C. or probably 4th-3rd millennium B.C. It shows men entering the presence of his gods, specifically a cult goddess Innin (Inanna), represented by two bundles of reeds placed side by side symbolizing the entrance to a temple.

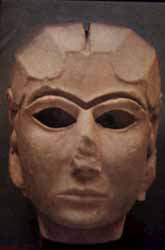

Inanna - Female Head from Uruk, c. 3500 - 3000 B.C., Iraq Museum, Baghdad.

Inanna in the Middle East was an Earth and later a (horned) moon goddess; Canaanite derivative of Sumerian Innin, or Akkadian Ishtar of Uruk. Ereshkigal (wife of Nergal) was Inanna's (Ishtar's) elder sister.

Inanna descended from the heavens into the hell region of her sister-opposite, the Queen of Death, Ereshkigal. And she sent Ninshubur her messenger with instructions to rescue her should she not return. The seven judges (Annunaki) hung her naked on a stake.

Ninshubar tried various gods (Enlil, Nanna, Enki who assisted him with two sexless creatures to sprinkle a magical food and water on her corpse 60 times).

She was preceded by Belili, wife of Baal (Heb. Tamar, taw-mawr', from an unused root meaning to be erect, a palm tree). She ended up as Annis, the blue hag who sucked the blood of children. Inanna in Egypt became the goddess of the Dog Star, Sirius which announced the flood season of the Nile."

Practically all Sumerian sculpture served as adornment or ritual equipment for the temples. No clearly identifiable cult statues of gods or goddesses have yet been found. Many of the extant figures in stone are votive statues, as indicated by the phrases used in the inscriptions that they often bear: "It offers prayers," or "Statue, say to my king (god). . . ."

SUMERIAN ARCHITECTURE

The beginnings of monumental architecture in Mesopotamia are usually considered to have been contemporary with the founding of the Sumerian cities and the invention of writing, in about 3100 BC. Conscious attempts at architectural design during this so-called Protoliterate period (c. 3400-c. 2900 BC) are recognizable in the construction of religious buildings. There is, however, one temple, at Abu Shahrayn (ancient Eridu), that is no more than a final rebuilding of a shrine the original foundation of which dates back to the beginning of the 4th millennium; the continuity of design has been thought by some to confirm the presence of the Sumerians throughout the temple's history.

Already, in the Ubaid period (c. 5200-c.3500 BC), this temple anticipated most of the architectural characteristics of the typical Protoliterate Sumerian platform temple. It is built of mud brick on a raised plinth (platform base) of the same material, and its walls are ornamented on their outside surfaces with alternating buttresses (supports) and recesses. Tripartite in form, its long central sanctuary is flanked on two sides by subsidiary chambers, provided with an altar at one end and a freestanding offering table at the other.

Typical temples of the Protoliterate period--both the platform type and the type built at ground level--are, however, much more elaborate both in planning and ornament. Interior wall ornament often consists of a patterned mosaic of Terra cotta cones sunk into the wall, their exposed ends dipped in bright colors or sheathed in bronze. An open hall at the Sumerian city of Uruk (biblical Erech; modern Tall al-Warka', Iraq) contains freestanding and attached brick columns that have been brilliantly decorated in this way. Alternatively, the internal-wall faces of a platform temple could be ornamented with mural paintings depicting mythical scenes, such as at 'Uqair.

The two forms of temple - the platform variety and that built at ground level - persisted throughout the early dynasties of Sumerian history (c. 2900-c. 2400 BC). It is known that two of the platform temples originally stood within walled enclosures, oval in shape and containing, in addition to the temple, accommodation for priests. But the raised shrines themselves are lost, and their appearance can be judged only from facade ornaments discovered at Tall al-'Ubayd. These devices, which were intended to relieve the monotony of sun-dried brick or mud plaster, include a huge copper-sheathed lintel, with animal figures modeled partly in the round; wooden columns sheathed in a patterned mosaic of colored stone or shell; and bands of copper-sheathed bulls and lions, modeled in relief but with projecting heads. The planning of ground-level temples continued to elaborate on a single theme: a rectangular sanctuary, entered on the cross axis, with altar, offering table, and pedestals for votive statuary (statues used for vicarious worship or intercession).

Considerably less is known about palaces or other secular buildings at this time. Circular brick columns and austerely simplified facades have been found at Kish (modern Tall al-Uhaimer, Iraq). Flat roofs, supported on palm trunks, must be assumed, although some knowledge of corbelled vaulting (a technique of spanning an opening like an arch by having successive cones of masonry project farther inward as they rise on each side off the gap)--and even of dome construction--is suggested by tombs at Ur, where a little stone was available.

The Sumerian temple was a small brick house that the god was supposed to visit periodically. It was ornamented so as to recall the reed houses built by the earliest Sumerians in the valley. This house, however, was set on a brick platform, which became larger and taller as time progressed until the platform at Ur (built around 2100 BC) was 150 by 200 feet (45 by 60 meters) and 75 feet (23 meters) high. These Mesopotamian temple platforms are called ziggurats, a word derived from the Assyrian ziqquratu, meaning "high." They were symbols in themselves; the ziggurat at Ur was planted with trees to make it represent a mountain. There the god visited Earth, and the priests climbed to its top to worship.

Most cities were simple in structure, the ziggurat was one of the world's first great architectural structures.

White Temple and Ziggurat, Uruk (Warka), 3200 -3000 B.C.

This temple was erected at Warka or Uruk (Sumer), probably about 300 B.C.It stood on a brick terrace, formed by the construction of successive buildings on the site (the Ziggurat). The top was reached by a staircase. The temple measured 22 x 17 meters (73 x 57 feet). Access to the temple was through three doors, the main located at its southern side.